Today Europe is facing the real possibility of socio-political and economic disintegration. While Europeans face internal and external crises of unprecedented proportions, politicians and policymakers in Brussels are struggling to keep the EU ship afloat in the midst of what some have begun to call the greatest political crisis in Europe since the end of the Cold War. In the face of these grim prospects one potential solution is rapidly gaining credibility and momentum: it is the case for Federalism in the European Union. Yet, while a federal reform could eradicate excessive bureaucracy and create coherence at the European policy level, it simultaneously has the potential to undermine the long-standing traditions and values that constitute the core of the European project, such as democratic legitimacy, national sovereignty, and the preservation of cultural identity and self-determination.

Could the Paris attacks have been prevented?

Five days after the attacks in Paris last November, I attended a public debate in the European capital of Brussels. During the discussion I asked Federica Mogherini, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, whether she believed the attacks happened due to flaws in Europe’s internal domestic security system. «How are we expected to fight terrorism», she answered, «when many member states still withhold parts of their security data?». Indeed, although organs such as Frontex have to an extent overseen defense and security at the supranational level, 28 national security agencies – one for each member state, each with its own operational policy – remain in place, many of which do not fully disclose their national security data. The flaws in this system are exemplified, for instance, by the absence of a shared database on suspected terrorists. As if the EU’s uncoordinated response to the migrant crisis wasn’t enough proof, the terrorist attacks in Paris have erased any doubts concerning the failure of cooperation on issues of internal security, border policies, and migration. Terrorism, like migration, is a global phenomenon and does not take national borders into consideration; why, then, would European security agencies continue to do so? This is not to say that terrorism is necessarily an external threat. On the contrary, in the case of the Paris attacks the terrorists were European citizens – many of them from Brussels. Yet, with the current legislative set-up, cooperation on security issues across European borders cannot function effectively.

Clearly, reform is necessary. The recent failure of the internal security system in Europe raises a volatile question: could the Paris attacks have been stopped if the EU had a central intelligence agency?

Yes, argues Guy Verhofstadt, former prime minister of Belgium and current leader of the Liberal Democrats (ALDE) group in the European Parliament. For decades, Verhofstadt has been a passionate advocate for further European integration and cooperation. His most recent book, Europe’s Disease, exposes the major structural flaws at the heart of the European Union and argues for a far-reaching federal reform of the system. What is more, the case for Federalism doesn’t restrict itself to security policy: according to Verhofstadt and other European Federalists, the key to solving all of Europe’s woes lies in Federalism. At a time when socioeconomic and political disintegration in Europe is rife, there is a strong argument to be made for further integration. Yet there seems to be confusion about what a federal United States of Europe would exactly entail and what the wider implications of such a union could be.

The proposed federal reform could have a large impact some of the most problematic policy areas in the EU today:migration and the economy

European Federalism

First and foremost it is important to understand why politicians and policymakers such as Verhofstadt are increasingly advocating for Federalism in Europe. The case for a federal Europe rests on the premise that a divided Europe is a weak Europe. In the broadest terms, a federal reform of the EU would therefore aim to create an economic and fiscal union, a banking union and a political union among the 28 member states. This would mean centralizing many aspects of political organization that are now largely decided by each member state individually. Currently, member states’ power to exercise national sovereignty often comes at a price, namely a lack of coherence at the European policy level. That is precisely what Verhofstadt means when he states «the problem is that there is not enough Europe.» Federalism in the EU would mean reforming current decision-making processes, for instance by changing the voting system in the Council of the European Union from unanimity to majority vote. At present, major policies affecting the whole of the EU can only be passed or rejected by the Council if all 28 member-states agree unanimously. Examples of policy areas that require unanimity are common foreign and security policy, citizenship and EU finances. Federalists argue that eliminating this requirement will shorten the period of deliberation and enable the executive branch to take decisions more quickly and effectively.

The proposed federal reform could have a large impact on many crucial issues, including some of the most problematic policy areas in the EU today: migration and the economy. The current refugee crisis could benefit from a federal approach to EU border policy. As a matter of fact, the Commission has recently submitted a proposal to the Council and the Parliament for the creation of a European Border and Coast Guard to better absorb the shock of the refugee crisis. Despite facing protest by some member states who are afraid of surrendering authority over national border policy to Brussels, the proposal’s logic is undisputable: the EU coastguard and border protection force would facilitate a coordinated operation at the European level. This federal approach could help untangle the yarn of bureaucracy that currently plagues EU border policy by harmonizing asylum laws and transit regulations, and by improving coordination among the relevant stakeholders. Arguably, a federal response to the current influx of refugees could benefit all parties involved in the crisis: governments, refugees, NGOs and civilians alike.

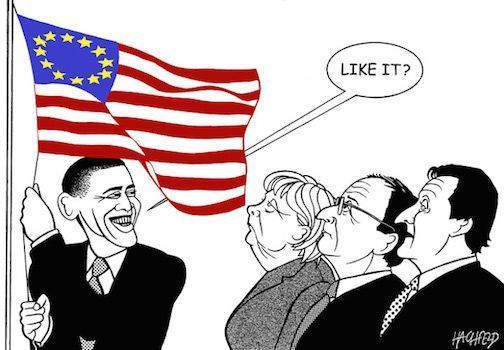

Imagen de Rainer Hachfeld en Vox Europ.

On the economic level, too, there is a case to be made for Federalism. Since the financial crisis of 2008, which originated overseas with the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble, Europe has struggled to keep its economy afloat. Somewhat ironically, the EU’s response to the financial crisis has been painstakingly slow compared to that of the U.S. Today, the U.S. economy is well on its way to recovery while Europe remains up to its neck in sovereign debt crises, austerity measures, skyrocketing unemployment and emergency bailout plans. According to advocates of Federalism, one of the explanations for the slower European recovery is the absence of a European equivalent to the U.S Treasury and the Federal Reserve. In the European Union, there is neither a common treasury nor a minister of finance dealing with economic and fiscal policy. Furthermore, unlike the U.S. domestic market, the Eurozone is not a single-bound market. According to the Federalists, this lack of integration and federal oversight makes it impossible to maintain a common Eurozone currency with seventeen different economic statutes.

The inertia of the European political economy becomes evident when one analyzes the European Union’s response to the economic recession and compares this to the one in the U.S. The failure of a minor economy such as Greece – which accounts for less than two percent of the EU’s GDP – has had major consequences and continues to threaten the collapse of the entire system. On the other hand, the bankruptcy of the state of Detroit never even came close to causing the collapse of the U.S. dollar. According to Verhofstadt and the Federalists, this is because the dollar is controlled by a strong federal state capable of implementing immediate measures. The Federalists argue that in order to establish and maintain a successful common currency, you need a common economic policy. In addition, you need a common space that is far more coherent and integrated than the European Union currently is, a goal that can only be attained if we were to federalize the EU economy to mimic the U.S. model.

Barriers in the way of a federal Europe

Even though there are obvious arguments in favor of a federal reform of the EU, there are significant barriers that stand in its way. Firstly, it is questionable whether a federal Europe would have any democratic legitimacy. Judging by the current political and social climate in Europe, a United States of Europe does not seem likely to be voted for any time soon. Virtually all EU member states are currently experiencing at least some level of Euroscepticism, separatism, or populist nationalism – many are seeing all three combined. There are myriad examples of populist reactionaries who are redefining the current European political landscape, from Marine Le Pen in France to Geert Wilders in The Netherlands and Viktor Orban in Hungary. Then there is the upcoming referendum on Britain’s EU exit (the Brexit), which can be interpreted as further proof of the popular discontent and democratic deficit present among European citizens.

One explanation for this popular sentiment draws support from the standard critique of representative democracy, namely that the further removed a government is from its people, the less popular support and democratic accountability it enjoys. Populists such as Marine Le Pen – whose Front National party is growing into a force to be reckoned with in France – understand this feeling very well. It was her father Jean-Marie Le Pen[*], previous leader of the party, who coined the phrase:

“I prefer my family above my friends, my friends above my neighbours, my neighbours above my compatriots, my compatriots above my fellow Europeans.”

This quote, besides being a clear expression of the most populist xenophobia, aptly represents what is perhaps the strongest argument against a more integrated (federal) European Union, namely that the people simply don’t want one. It is worth noting, however, that the statistics depict a different reality. In the 2013 Eurobarometer, 46% of respondents supported the creation of a united EU army. Moreover, 44% of respondents supported the future development of the European Union as a federation of nation states while 35% opposed the idea. Though statistics such as these are by no means conclusive and must be taken with a pinch of salt, they do provide an interesting counterweight to the widespread idea of a European democratic deficit. Indeed, these figures suggest that there is a significant degree of democratic support for further federal integration in the European Union. This implies that if the EU is indeed going to steer towards Federalism in its future course – which it already seems to be doing – a lack of democratic legitimacy may not be as significant an obstacle as Euro-sceptics claim.

Another impediment for Federalism is the concern over national sovereignty. One could argue that the beauty of the European Union lies in the capacity of its members to preserve their national sovereignty while simultaneously enjoying the mutual benefits of the EU. In the decision-making arena, a federal reform of any proportion is likely to undermine national sovereignty by centralizing power into the hands of the executive branch. A clear example of this is the Federalists’ proposal to change the voting mechanism in the Council from unanimity to majority vote, a reform that would almost certainly undermine the bargaining position of many member states, particularly the smaller and less influential ones.

The true desirability or success of a federal Europe can only accurately be assessed if we incorporate matters of culture, social values and national identity in our assessment

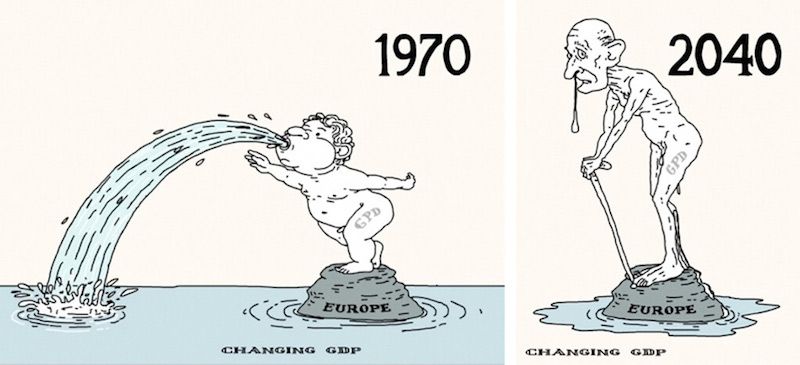

Imagen de Joep Bertrams en Vox Europ.

Yet the problem exceeds this legislative aspect; a more important concern is the effect that federal integration could have on the social identity of European societies and citizens. Indeed, there seems to be a palpable tension between integration on the one hand and self-determination on the other. This contradiction is inescapable: is it realistic to strive for legislative harmonization and integration in a Europe that is – despite significant achievements – still marked by stark national differences in culture, religion, language and overall social values? In a similar vein, it seems unrealistic to compare Europe to America in the context of European Federalism because the two systems do not share the same legislative (not to mention cultural and linguistic) complexities. The historical divisions and brutal conflicts that have plagued Europe since its inception have shaped the EU into an elephantine bureaucratic union of separate and often opposing parts, a union that has managed to co-exist in collaborative harmony for a relatively short period of time. In many ways, the Federalists raise valid concerns about the lack of coherence in policy and legislation, but this lack of coherence must be seen as a manifestation of deeper social divisions. It is not at all certain that a federal reform will be the appropriate mechanism to address these issues. Federalism appears to be an excellent solution when the matters at hand are pragmatic, quantifiable discussions about specific common policies. The reality, however, is that the debate is not simply about an integrated EU economy or the harmonization of borders; the true desirability or success of a federal Europe can only accurately be assessed if we incorporate matters of culture, social values and national identity in our assessment. In short, when this unquantifiable social dimension is included, the case for Federalism appears to be less clear-cut.

How much integration is desirable?

The Federalist approach is one of pragmatism and realism. Aware of the EU’s declining geopolitical influence and under threat by unparalleled global competition from the powerhouses of the developing world, policymakers are now seriously debating about the potential benefits of a federal Europe. Indeed, policies containing major federalist elements are increasingly being propagated by both the European Commission and the European Parliament. For instance, the digital single market and the common agricultural policy are both proposals that aim to harmonize legislation to increase competitiveness and eradicate excessive regulation within the EU. In the same vein, the controversial TTIP (or Transatlantic Trade and Investment Pact) follows the logic of Federalism by advocating for decreased national regulation (in the name of efficiency) and a more open EU market to facilitate trade and investment.

At the same time, the European Union remains the global symbol of social democracy. Where America is seen as the world’s superpower (though this perception is rapidly changing) and Asia is associated with innovation and growth, Europe’s assets are its rich history, its cultural and linguistic prowess and, most importantly, its welfare states. If there is one flagship the EU can sell to the rest of the world, it must surely be the delicate balance between prosperity and solidarity, between liberalism and socialism, a balance achieved by decades of consensus-building. Though it may well be possible to preserve national autonomy while creating further federal integration, one cannot help but wonder whether, in the long run, a United States of Europe would have a detrimental impact on the melting pot of culture, nationality and language that is the EU. Could the harmonization of economic practices and the blurring of borders eventually lead to an unintended harmonization – read homogenization- of other areas of society? It is a possibility that needs to be considered.

[*] ^Correction: An earlier version of the article mistakenly attributed the quote to Marine Le Pen, when, in fact, it was her father who said it.

I hope I live to see a Federal Europe and not through a third nationalistic war. Say what you may, be you an Englishman or a Pole, but nationalism is one era outdated. We live in a meritocracy, and I believe/will always believe the best gets the spot, no mater their origins, and whether someone likes it or not, that’s as fair as it gets. I’m not a fan of socialism, and in my views welfare is like a cancer for peoples mindset, because they accept conformity. Not only that, they become dead weight for productive people. I may not agree with some of Brussels decisions, well I actually only agree with a few…but why? Because they can’t make the right decision when there are 28 countries to disagree because of personal agendas! Forget Brussels, let the people elect someone! Give the people reasons to be interested in politics! Reward the act of thinking and dissuade irrational populism! Europeans aren’t foreigners in an European country either, and to say culture and identity would suffer under a federal state is nothing but fear-mongering. We would see the birth of an European identity, second to the «state» identity. Another issue is simple-minded people saying it’d be undemocratic to have the current EU government rule a state.(Well, no shit Sherlocks aren’t you bright ones) We don’t live in a federal state yet, and to be able to there would have to be massive changes, most likely redesigning everything. Backward thinking is a loud minority and there is no information what-so-ever on the federal issue, so no wonder people choose populism, they’re the ones who go to the people themselves! On the British issue, let them chose their future, as well as them letting everyone else chose theirs(Scottish and N. Irish included). Inform them of the pro’s and con’s, and let them chose, but don’t use this as a tool to make 27 countries have even more trouble.

On the economic issue, the USA is the best example. Unity brought prosperity, but in Europe, the land with the brightest people, is still suffering because of idiotic nationalistic decisions…Why would someone ever think about killing the one thing that made the EU so successful?(no borders) Because the lack of unity in the refugee issue got 200 people killed in the EU(and hundreds of thousands in Syria but forget that, right..? Let’s even forget the reason they’re coming here in the first place!) We don’t need to absorb the refugees, we need to fix the reason they’re running for their lives. No? oh well then, close the borders until they’re so many you’ll have to shoot them and make your borders common graves, and let the IS behead children and women in the false pretext of a god. That makes the so-cald Euroskeptics beter than those extremists right? oh…..well…